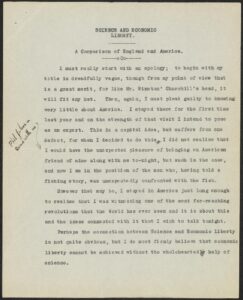

Download the PDF of Whitehead’s essay “Science and Economic Liberty: A Comparison of England and America” here. This document comes to us from MS 282, Special Collections, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University, who have kindly allowed us to share it for this reading group discussion.

Video of Discussion

Background on “Science and Economic Liberty”

The occasion for which this address was written is not known, and it is not dated, but we do know that it must have been written and delivered sometime in 1923, since Whitehead says on the first page that he “stayed there [in America] for the first time last year.” Unbeknownst to many Whitehead scholars, he had in fact visited America in April 1922 prior to his fall 1924 migration to Harvard. Volume 2 of Victor Lowe’s Whitehead biography describes the trip:

They had never been to America. The occasion was a festival to honor Charlotte Angas Scott on her retirement as Professor of Mathematics at Bryn Mawr College. She was English, had been at Bryn Mawr since 1885, and had published some mathematical books and papers. She had studied at Girton, where the day in 1880 when Cambridge announced that she had made a score in the Mathematical Tripos equal to that of the Eighth Wrangler was celebrated. (As Cambridge did not give degrees to women, her B.Sc. and D.Sc. were from the University of London.) Whitehead conveyed the greetings of Girton’s staff and read a paper, “Some Principles of Physical Science,” dedicated to Miss Scott; it was reprinted as Chapter IV of his Principle of Relativity. The Whiteheads returned to London as soon as the festival ended, but they had fallen in love with America. (Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and His Work, Vol. II, page 83)

Girton was a women’s college at which Whitehead taught, probably without pay, for about 25 years, in addition to his teaching load at Trinity College (Lowe, vol. 1, p. 160, 217).

During his trip to Bryn Mawr, Whitehead very likely visited with Theodore and Grace de Laguna, a married couple who were both professors of philosophy there. Theodore had reviewed Whitehead’s PNK in 1920, and in 1922 wrote an article which suggested a way to reform Whitehead’s “method of extensive abstraction.” Whitehead would later credit Theodore de Laguna with making the Process and Reality treatment of extension possible (Lowe, vol. 2, p. 177, 237). After Theodore’s death in 1930, the Whiteheads kept in touch with Grace; two letters of hers to Whitehead written around his 80th birthday in 1941 are held in WRP’s archives.

Whitehead writes in the left margin of the first page that “Phil Johnson came with us.” This appears to be Philip C. Johnson of Cleveland, Ohio, who would go on to become a famous architect. Born in 1906, the son of wealthy lawyer Homer Johnson, he would have been just 16 at the time of this address. He enrolled at Harvard in 1923, majoring in philosophy, but it took him until 1930 to graduate, and by that time his attention had turned to architecture. Whitehead’s grading notebook lists Johnson’s name for his fall 1927 Philosophy 3b lecture course.

Whitehead would not be made aware that Harvard was looking to hire him until the second day of 1924, via a letter from Mark Barr, and so Whitehead would not have had any notion about moving to America at the time this address was delivered in 1923.